It was Day 2 of the new school year.

The bus stop is a three-minute walk from our house. Dylan’s bus was scheduled to arrive at 7:10.

Dylan left the house at 7:09.

Even at 7:09, he stopped in the middle of the driveway, and asked whether or not I thought he could go back inside, run upstairs, find his ear buds, and still make it to the bus stop.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea,” I said.

“I think I could do it,” he said.

I was watching to see if the bus might whiz past. He was still thinking about the ear buds.

“You have one minute to get to the bus stop,” I said. “I don’t think it’s a good idea.”

“Whatever,” he said, and started strolling toward the bus stop.

The phone rang three minutes later.

“Hello?”

“There’s like nobody here,” Dylan said from the bus stop.

“Perhaps you missed the bus,” I said.

“How could I have missed the bus? I left in plenty of time!”

“You didn’t leave in plenty of time,” I started – but was interrupted by the shrillness of his voice.

“I did leave in plenty of time! The bus could not have been here at 7:10 or I would have seen it!”

“Maybe the bus came early,” I said.

“Why would it come early?!” he wailed.

Like it was my fault he missed the bus.

Dylan walked back home and rode with me while I took Shane to school. I’ve told him before that if he misses the bus, he can ride with us – but his school starts earlier than Shane’s, and we would have to get Shane to school first.

Traffic was atrocious. We stopped along the way to mail a letter, then looked futilely for Shane’s friends, then drove back up the street to drop off Shane with some other friends.

Then I dropped off Dylan at his school, which is semi-walking distance from Shane’s school. Miraculously, Dylan arrived for his second day of school just as the last bell was ringing.

No natural consequences for his behavior.

The next day, he missed the bus again. I got the call from the bus stop.

“So I left three minutes earlier today,” he said. “And there’s only like one person here.”

“Okay,” I said. “Maybe you should have left more than three minutes earlier.”

“Why would I need to leave more than three minutes earlier?” he shrieked. “I was here in plenty of time if the bus was coming at 7:10!”

Sigh.

“Did you ever consider,” I said, “that maybe the time was changed and that you somehow missed the announcement?”

“I didn’t miss the announcement,” he said. “Everybody was listening to music. So everybody would have missed the announcement.”

“Perhaps you should have left way earlier today to see what time the bus actually plans to arrive. There’s another person there, right?”

“Not anymore,” he screeched. “She left! Why should I come way earlier if the bus is supposed to be here at 7:10?!”

“Why don’t you come home…”

“I am coming home!” he screamed.

Like it’s my fault he missed the bus.

Dylan walked home. I drove Shane to school and Dylan rode along. And then I dropped off Dylan at his school.

Miraculously, Dylan arrived at school just before the final bell.

Summer has – once again – completely bypassed me somehow.

I remember that we went to see Finding Dory on the last day of school, after which I swore that we would go swimming every week during the summer. I didn’t want to miss anything. Then, with only two days of summer vacation left, we finally spent two hours at a swimming pool.

Where did the summer go?

Our vacation was brief – albeit jam-packed with activity. In seven days, we saw eight colleges. We visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and two huge amusement parks over the course of three days. We even stopped to ride the world’s oldest coaster. For the first time ever, our vacation was filled with enough roller coasters.

But the kids also went to camp for a week, an experience they absolutely treasured. Bill and I had “date week” while they were gone, and stayed at a B&B, and ate ethnic foods and went to fancy restaurants, and became spies at the International Spy Museum.

Dylan spent a week on a mission trip to serve less fortunate folks in West Virginia – and came back muscular and serene. Meanwhile, Shane entertained preschoolers at Bible School in the mornings, then he worked in the evenings as a junior mascot for a baseball team. I played a lot of softball, and we went to a lot of baseball games.

We went zip-lining through the trees – twice. We went tubing down the river – twice. We took walks in the woods and went to the movies and visited farmers markets and played ball and went to escape rooms and the library and the dog park and the playground and the pool. We shopped at the mall and went pedal boating and played miniature golf and hit softballs and ate ice cream and chili dogs and fried brownies and popcorn and burgers and pizza and sweet corn and fresh-picked tomatoes – and then we ate more ice cream.

We went to the county fair twice. Shane won prizes for his photography. Dylan sang karaoke, and he sang for school kids and for seniors. Dylan and Shane both earned more than 50 student service learning hours toward graduation. Oh, and they somehow finished their summer homework. They read books and wrote music and made lists of their favorite things. They had friends over for playdates. We all played board games and saw some spectacular concerts.

For maybe my favorite Norman Rockwell moment of the summer, the boys and I sprawled on the porch at midnight and watched shooting stars fly across the night sky during the perseid meteor showers.

Okay. I think I see where summer went.

We had fun.

I am sorry that it’s over.

But that’s how summers are supposed to be.

I have been agonizing with what to do.

School starts on Monday, and I wanted very badly to let Dylan “do it all himself.” I want to go an entire year without contacting his teachers, without asking him if he’s done his homework, without checking every day to see if he’s doing what he’s supposed to be doing.

We start the school year with a contract for each boy. The contract outlines expected behavior, and consequences of behavior that is inappropriate or otherwise detrimental to their own lives. I’ve delayed creating the contract because while my head is begging me to let this be THE YEAR that Dylan does what he’s supposed to do, this is entirely dependent on Dylan suddenly outgrowing the behavior that has been with him since he was in fourth grade.

Dylan is also preparing to drive a car. In a few weeks, he’ll be old enough for his learner’s permit. But having his learner’s permit does not make him responsible enough to drive a car – no matter how well he’s done in his go kart.

In fact, the go kart is sitting in the garage waiting for Dylan to put a new belt on it. It’s been broken for the entire summer, and Dylan claims that he hasn’t “had time” to fix it. Surely, ten minutes of those 7,000 hours he spent playing the keyboard could have been spent fixing that go kart.

It’s a fine example of how Dylan is not quite responsible enough to drive a car.

So I am thinking that we make his driving privileges contingent on his ability to know when a test or a quiz is taking place, to know when he’s got homework – and (perhaps a miracle will happen!) when to turn it in.

I don’t want to take away his phone anymore. I don’t want to take away his music time. I don’t want to take away his voice lessons. And his favorite job in the world is coming up, too – scarer at Field of Screams. I would never, ever want to take that away from him.

But if Dylan can’t remember to turn in his homework, how will he ever remember to turn on his turn signal, turn his head and look into his blind spot, and glide over into the next lane calmly? If he can’t study because he’s too distracted by Snap Chat, how can he drive a 3,000-pound vehicle down the road without Snap Chatting? If he can’t handle 10th grade, how can he handle a car?

Hm. I think I may have inadvertently discovered the answer we’ve sought for so long.

We can wait for Dylan to drive until Dylan proves that he’s mature and responsible enough to handle something simple – like school. And I don’t mean “remember your homework for a week and drive forever,” either. I mean, “BE responsible, so we’ll know you’re a responsible driver.”

This may be the only way to move forward – and save his life.

Even if he doesn’t like it.

The school year is fast approaching. I am a little sick about it.

Shane is not looking forward to returning, although he misses his friends. But my major concern is my eldest.

While Dylan and I have not had a positive, rewarding summer, I have enjoyed watching him as a happy, fun-loving member of the family. Sure, we’ve had our arguments about him taking responsibility for himself. And I’ve been rudely reminded to back off a few times. But for the most part, Dylan is so much happier when he’s not in school.

This is not to say Dylan is not happy when he is working. In fact, he’s been working quite a bit this summer, and he’s been very happy. He’s been singing at the senior living centers. He’s helped to rebuild a home in West Virginia. And he’s volunteered at baseball games, sung for school children, and written numerous songs. He’s been very busy – and that is what makes him happy.

But he hasn’t been forced to sit still for seven hours a day. That starts again soon.

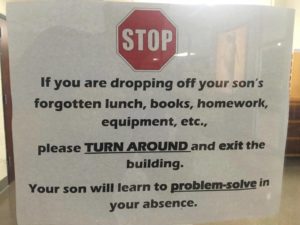

A friend posted a reminder on her Facebook page. It was a photo of a sign that was posted at a school. It said:

This is the reminder I will need every day of the school year. It is Dylan’s job to remember what he needs for school. It is Dylan’s job to remember what he needs to bring home for homework. And it is Dylan’s job to do that homework, turn it in, study for tests, remember that there are tests, and know what is needed to succeed.

He simply doesn’t know. And I have spent far too long finding out for him, then relaying that information to him.

Dylan goes to college in a few short years. He needs to know – on his own – how to succeed. He needs to find the methods that work for him.

And I need to back off, and let him learn.

Dylan was getting ready to perform again at the senior living community.

Given that he sang a number of songs that residents didn’t know in his prior performance, I suggested that Dylan sing some songs from the 1940’s, since those are the songs best known by people whose average age is 85.

“Okay,” he said without flinching.

“Do you want me to get you some karaoke CDs?”

“YES!” Dylan said. (Since most of our communications are via text, I know that he said this emphatically, in ALL CAPS.)

So I spent yet another $15 on yet another karaoke CD. And when it arrived two days later, I made note of the six songs most likely to be known and loved by people in that senior residence. Dylan took the CD upstairs to his “studio” and started learning the songs.

Or so I thought.

Three days later, Dylan could only sing five words: “I did it MY WAY.”

“It’s the only one of those olds songs that I like,” he said.

“What about the other songs?” I asked. “Aren’t you learning those?”

“No,” he said. “I’m not going to sing songs that I hate.”

“But they are songs that the residents are going to love!” I shrieked. “You need to do the songs they like, not what you like!”

“Performing is a cooperative effort,” Dylan said. “I will sing some songs that they like and some that I like.”

“They don’t even know the songs that you like,” I said. “I thought you wanted them to be happy!”

“But I’m not going to sing a song I hate!” he said. “I’m the performer and I think I know what are the best songs to perform.”

The argument went on longer than it should have.

This is why you will not be able to have a career in music, I wanted to say. You don’t think about them. You only think about you.

I wanted to say, No one is going to want to see you perform if you don’t do what THEY like. I wanted to say, Performing is about giving of yourself, not having a fun time and showing off how great you are.

I remembered Dylan declaring – for years – his loftiest ambition: “I just want to make people happy with my singing.”

But now that ambition has taken a back seat to his teenage will: I want to do what I want to do, and if you don’t like it, I don’t care.

A few weeks ago, I watched those senior living residents closing their eyes, hands to their hearts, singing along with the TWO songs they knew, dreamily diving into the music they loved so well. They were so incredibly happy for those six minutes.

Music is therapeutical. It can transform people from the space they’re in to a whole different time, in just a few seconds. The people in that community can go from being stuck in a nursing home to sitting in the front seat of a 1949 Ford pick-up with just a few notes.

And maybe Dylan will sing those two songs for them again this time. So for those six minutes – out of an hour – they will be transformed. But it sure won’t be a performance designed to make them happy.

It will be a performance designed to make Dylan happy.

And the Ford pick-up will have to wait and find them in their dreams.

Shane entered four of his photos into the county fair competition. So we went to the county fair to see how he’d done.

We went to the arts building, and finally located the wall labeled “Children’s Photography.” There were about 200 photos on that wall, many stuck with ribbons to designate what award they’d been given. We were happy that the judging had been done before we’d arrived, so we knew whether or not Shane’s photos had been recognized.

Shane found three of his photos right away. “I got third place for my picture of the camera!” he exclaimed. “And fifth place for my water fountain!”

He found the squirrel in the “Wildlife” section – which was a very popular section. The squirrel photo was awesome. I’d been trying to capture a squirrel in action for thirty years and had never taken a photo that good. “I got Honorable Mention for my squirrel,” he said.

We all scoured the wall for his fourth photo, which was in the “Buildings and Memorials” category. We couldn’t find it.

I thought maybe they’d lost it, somehow, during the insane submission and judging process. We kept looking, to no avail.

I remember when Shane took that photo. It was a photo of the Bennington Battle Monument, in Vermont. We’d stumbled upon it over spring break, while trying to find Robert Frost’s gravesite which we never did locate. The monument is more than 300 feet tall, and towers above everything for miles.

Shane took half a dozen photos of it – but what he was doing was just odd. He was pointing the camera toward the monument, and waving his hand in front of the camera. With his left arm in the photo realm, he was manipulating the camera with only his right hand.

I was baffled, watching him. He looked like he was doing some kind of ritualistic dance.

“What are you doing?” I finally asked.

“I’m taking a picture,” he said. Then he showed me the digital images on the back of the camera. In the photo, it looked like Shane was picking up the monument. Using perspective, he was able to make it look as though his hand was actually around the entire 300-foot monument. And the way he framed it, he could have been carrying it away.

After we’d matted all four photos, Shane and I liked the monument best. But we couldn’t find that photo on the wall.

Finally, we asked a fair volunteer if maybe that photo was lost.

“Did you try the Champions wall?” she asked.

“The what?” I said. We had never heard of the Champions wall, so the volunteer pointed the way.

We all raced over to a board labeled “Photography Champions.”

And there, on the wall, was Shane’s photo of the Bennington Battle Monument being carried away. It was one of only three children’s photos to be selected for the Champions wall.

Shane won the Chairman’s Choice Award.

While we were snapping photos of Shane next to the Champions wall, my eyes were so full of tears that I could barely see the photos I was taking.

I’ve been crying for years, every time my son walks out onto a stage. But I’ve just realized that these tears are not necessarily only tears of joy.

They are tears of pride.

Dylan signed up to sing for the elderly residents of a local nursing home.

“I really just want to help people,” he told me. So I gave him a choice of two dozen volunteer opportunities, and he decided to sing.

When they emailed him, they said he needed a TB test and a volunteer application.

I told him to call for the TB appointment. He set it up – but then we had to reschedule for some reason, so I rescheduled it.

He had the test and results in less than a week. Meanwhile, he signed up with another nursing home – and this one required a TB test, an application and an hour-long orientation.

So Dylan decided not to do any singing for either place until he finished the orientation – which was in May.

It took him six weeks to commit to a date at one of the places. It took him another two weeks to show up and sing.

And that’s all he did: show up and sing.

He didn’t contact the place in advance, to confirm that he’d be there. He didn’t know the name of the person with whom he’d been communicating. He woke up at 10:30 for an 11:00 gig. He brushed his teeth and his hair, but he didn’t bother to shower. He only ate breakfast because I made him a sandwich to eat during the five-minute drive – but he had trouble choking it down, because he was too busy writing out his set list – the one I’d told him he needed to do at least two days prior to the event.

Dylan said that he spent hours “getting ready” to sing. He played the keyboard and sang songs for hours and hours and hours and hours. We suggested old spirituals, since that’s what the home recommended, and taught him popular songs from decades ago, like Bicycle Built for Two and Let Me Call You Sweetheart.

But Dylan had other plans. He downloaded the lyrics to How Great Thou Art on his phone, and read them while he sang. He only knew one verse of Amazing Grace. He sang at least one pop hit, a few songs from the eighties, and a song from the sixties – by The Monkees – even though he didn’t know how the song went.

He’d planned to spend far more time playing the piano than singing, even though Dylan doesn’t actually play the piano. He doesn’t read music, and he doesn’t look up from the keys when he plays. And while his voice is wonderful and his piano playing isn’t bad, the combination knocks him completely off his game.

His strength is in his voice.

When I finally encouraged him to come out from behind the piano, Dylan started to really sing. Staff members came out of the woodwork and started to dance. Residents started swarming into the room. There were song requests. People from all walks of life were looking down from an overlook upstairs, smiling and pointing.

Dylan was a hit.

When it was over – and in spite of Dylan’s insistence on singing songs for which he had no preparation – the staff begged him to come back.

And in spite of his unprofessional demeanor and inability to prepare, I suppose I’ll take him back again someday.

Every time I open my mouth, Dylan jumps down my throat.

For example I might say, “Dylan, you are walking out the door without shoes. You need shoes.”

“No I DON’T need shoes,” he will growl. “No one’s going to throw me out of the store for being barefoot.” Then he will stomp on.

This example didn’t actually happen, but you get the idea. If I speak to Dylan, we get into an argument.

So I decided to try a new way of communicating. I would no longer speak, except to say one thing: “You’re right, Dylan. You are always right.”

Dylan is not always right. In fact, Dylan is wrong quite often.

I try to admit when I am wrong. Sometimes it requires a phone call, an internet search, and/or a trip to the library to prove that I am wrong – but truly, I am often wrong. And I will say, “Wow, I was wrong about that.”

But Dylan refuses to admit that he is ever wrong. Therefore, arguments abound. If anyone disagrees with someone who is always right, there is no winning the argument – no matter what. Dylan is very smart, and can make even the tiniest tidbit into a day-long debate to prove this correctness.

But I can’t just sit around saying, “You’re always right.” I also have to make known my expectations for Dylan’s day.

So when I have something to say to Dylan, I write it down. He has been getting a note every morning with a list of expectations and responsibilities. When he has chores to do, they are on the list. If I want to tell him something I’ve been thinking about, it goes in the note. And every morning, since I wake up thinking about what I need to tell Dylan, I just write it all down – once – and I’m done for the day.

Then, when we are spending time together, the only thing I say is, “You’re right, Dylan. You’re always right.”

This morning, Dylan came downstairs to go to the fair – the outdoor county fair – in the hundred-degree heat. He came downstairs at 9:30, having not yet eaten breakfast, to walk out the door “at” 9:30. He is wearing black, which absorbs heat more than any other color. He is wearing warm socks and high-top sneakers. He is going to roast and sweat like one of the pigs in the county fair pens.

But I am not saying a single word. Nor will I mention it in tomorrow’s note. Because until further notice, Dylan is always right.

I have a friend who is very artsy, and her daughter, who is Shane’s age, is also an artist. Last year, the daughter entered her art into the county fair competition.

So Shane decided he wanted to enter the competition, too. He is a very skilled photographer.

Shane chose four photos to put on display at the fair. The rules are very strict, as to sizing, matting and overlays. Participants must follow the guidelines, or photos will be disqualified.

I am not an artist, but I am a skilled shopper. To mat Shane’s four photos, I bought 50 mat boards, 25 white overlay mats, 10 black overlay mats, and a can of spray adhesive.

Then we went to work. With Shane’s gorgeously enlarged photos, we spread out our supplies on the table.

Let me backtrack a moment to say that my friend – the one with the artsy daughter – has the best parenting style of anyone I’ve ever met. She is positive and encouraging, and allows her kids to actually do whatever they can do. As a result, they do a lot, quite independently and very well.

So, wanting to imitate her awesome parenting, I put Shane in charge. He chose the mat boards and the appropriately colored mat overlays. He figured out where he wanted to place the photos and marked the mat boards with pencil.

He read the directions on the spray adhesive. Then, with carte blanche from me, Shane opened the can of adhesive, held it six-to-eight inches from the mat board, and started to spray.

Within two seconds, it looked like a smoke bomb had exploded. We could barely see the mat board under the flying spray. Shane kept stopping and starting, afraid that he was doing something wrong, but I encouraged him to keep going.

“Use as much as you need,” I told him with a shaky smile, wiping the flying glue from my hair. “Just make sure you do the edges, too.”

Big blobs of white goo formed on the mat board, while an aerosol-rubber smell filled the room. He sprayed and sprayed and sprayed, but the top left corner was still completely empty.

“Don’t miss the top right corner,” I said, forgetting that my right was his left.

Shane sprayed more blobs on the left side. “Oh sorry,” I said. “I meant the left side.” He caked the left side in glue.

Finally, the spray stopped.

“Okay,” I said calmly. “Put the photo by the pencil marks you made.” I looked at the board, where the pencil marks had been devoured by spray adhesive.

Shane dropped the photo in the mess. He slid it around as much as he could in the glue, trying to place it correctly. The adhesive had started to dry, and nothing was moving easily. His hands were covered in glue. My hands were covered in glue.

I handed the mat overlay it to Shane, and he shoved it down on top of the photo. There was glue on the photo, glue on the mat, and nearly a full inch of glue on the table, two square feet around the finished project.

I grabbed a wet paper towel and wiped some of the glue off the photo, while Shane got more wet paper towels. My hands were nearly embedded in all the glue on the table. We tried to save the photo, the table, the chairs, our hands, our clothes, our hair.

Five minutes later, the area was as clean as it was going to get.

“Okay,” I said to Shane. “Which one do you want to do next?”

During our vacation, we spent one evening at the beach.

It was low tide on a Great Lake, so the little waves went on and on and on. When we first walked into the water, which was calm and warm, the water went up to our ankles. We walked a bit further and it went up to our knees. We walked a long, long, long way – and it went up to our waists.

The kids had fun jumping and splashing in the waves, but I got tired and went in to sit and watch the sunset from the sand. A little while later, Shane got out of the water, and Bill took him to the nearby swimming pool.

Dylan stayed in the water, so I stayed on the sand to make sure he was safe.

I’d told Dylan about drop-offs, and how he had to be careful to stay close to shore. But the waves went way, way out into the water. And Dylan went way, way out into the water, too. With every wave he jumped over, he went a little bit further. The water was only up to his chest, but the waves kept rolling in, so I could only see his head bobbing above the waves.

Sometimes, I couldn’t even see his head.

And as I sat on that chair in the sand I thought, This is how it’s going to be.

As he drifted further and further away from shore, jumping wave after wave and having a great time, I realized that I had two choices. I could race out into the water and drag him back in to shore, or I could sit and watch while he did whatever he was going to do.

And in life, I realized, those were my choices, too.

In my opinion, Dylan wasn’t making a wise decision to go so far out. But Dylan – who has never known anyone to be swept away by an undertow – thought he was making a fine decision. He thought he could handle the Great Lake on his own. He’s tall, and strong, and – like most teenagers – utterly invincible.

I have to let him go, I thought. I have to let him make his own choices, and do his own thing. I have to let him go.

And I sat on the shore and I cried. I cried because I know he’s going to make really stupid decisions, and that I won’t be able to stop him. I cried because he could quite literally die if he makes those stupid decisions, and I will never see his beautiful smile again.

Then I remembered that what happens is God’s will, not mine. And I prayed my standard prayer: “Please keep him safe and healthy, God. Please keep my child safe and healthy.”

I repeated it like a mantra while the tears rolled out from under my sunglasses, and the sun disappeared leaving the sky full of bright, gorgeous colors.

Eventually, I stopped crying and just watched.